About the exhibition:

"Shadow Stories and Matters of Time" brings together three contemporary artists, Sita Kuratomi Bhaumik, Christopher Myers and Kambui Olujimi, who focus on the transformative aspects of storytelling, time, migration and light, as metaphors for contemporary realities. Through found materials and crafted objects, each creates narratives that reflect lived experiences and make social commentary that references recent and historic events related to issues of race, migration and social justice.

The exhibition is curated by artist Hank Willis Thomas as part of For Freedoms, an organization that believes citizenship is defined by participation, not ideology. Through nonpartisan nationwide programming, For Freedoms uses art as a vehicle for participation to deepen public discussions on civic issues and core values. For Freedoms is a hub for artists, arts institutions and citizens who want to be more engaged in public life.

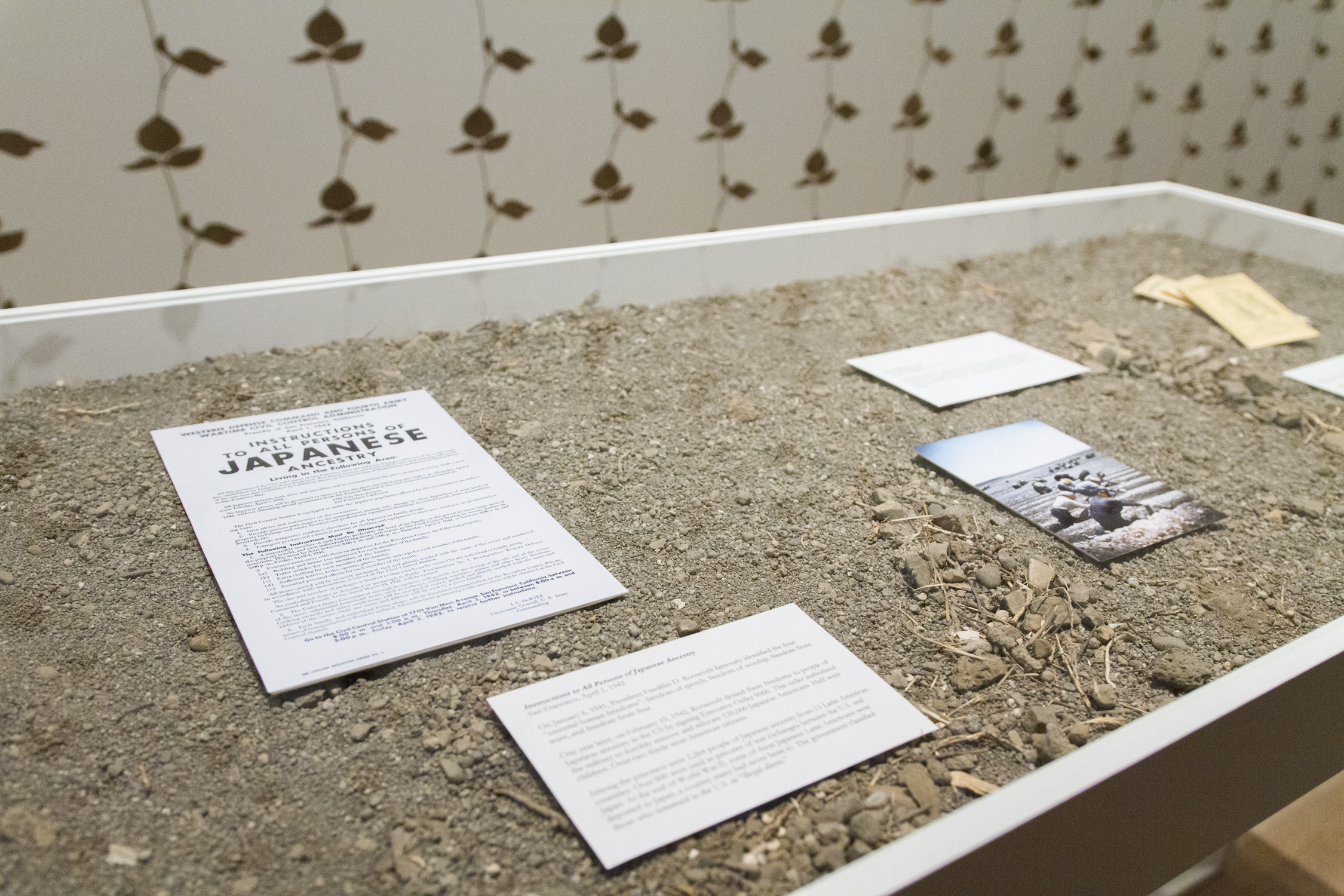

The exhibition includes a site-specific wall installation, The Archive of Dust, utilizing soil from Tule Lake Relocation Center, an internment camp in California near the Oregon border that had a peak population of 18,789 people of Japanese descent from 1942 to 1946. The work brings scrutiny to the forces of xenophobia that haunt the present.

Many thanks to Mark Baugh-Sasaki for a loan of 300 lbs of dust from Tule Lake that made this installation possible.

The Places Where the Answers Were: The Archive of Dust

CAPTIONS

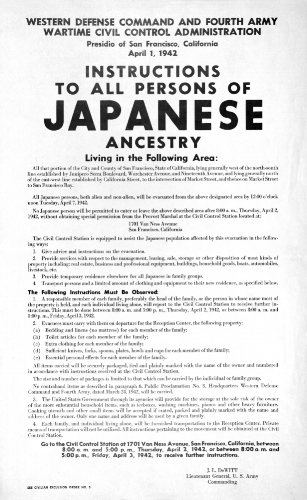

Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry

San Francisco, April 1, 1942

On January 6th, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt famously identified the four “essential human freedoms.” Freedom of speech. Freedom of worship. Freedom from want. Freedom from fear. One year later, on February 19th, 1942, Roosevelt denied these freedoms to people of Japanese ancestry in the US by signing Executive Order 9066. This order authorized the military to forcibly remove and relocate 120,000 Japanese Americans. Half were children. Over two thirds were American citizens. Among the prisoners were 2,264 people of Japanese ancestry from 13 Latin American countries. Over 800 were used in prisoner of war exchanges between the US and Japan. At the end of the war, some of these Japanese Latin Americans were deported to Japan, a country many had never been to. The government classified those who remained in the US as “illegal aliens.”

Men Working in Field

Tule Lake Segregation Center, c.1943

Library of Congress

In operation from 1942-1946, the camp at Tule Lake was located in California near the Oregon border. Of the ten Japanese American concentration camps, Tule Lake was the only Segregation Center. This meant that Japanese Americans deemed disloyal, based on their answers to a controversial questionnaire, were sent to this camp.

The Archive of Dust

Dust from Tule Lake Segregation Center applied directly to wall, 2018

“That dust would crawl up like ants through those cracks.” - Jimi Yamaichi

Kitazawa Seed Company

Est. 1917

Before WWII two thirds of Japanese Americans worked in agriculture and grew 40% of the vegetables in California. In the camps they earned $12 a month, a quarter of the average pay for farmworkers at the time. At its peak, Tule Lake produced over 10,000,000 pounds of produce in 1943. Some of this produce was sold on the open market.

It was no accident that the newly formed WRA hired administrators from the Department of Agriculture; camp locations were in part selected as trials in turning dust storms into fertile soil.